Welcome to what is quite possibly the very first article for Universal Aesthetics!

It is intended as the first part of the series of peeks into the world of nutrition and will cover everything you need in order to successfully manage your weight.

[space_20]

When I considered what are the necessary things you should be able to find on my site – stuff you ideally should know about and understand fairly well before venturing into this whole fitness and healthy lifestyle business, my first thought was – the importance of diet. The word „diet” has become synonymous with losing weight however the word itself is derived from latin and at it’s core means „daily food allowance” or simply „daily nutrition”.

The point of this article is to provide you with tools to help assess your need for calories and macronutrients – your daily nutrition – in order to optimize body composition changes and help with progress towards your personal goals.

I don’t believe there is anything remotely as beneficial to health and sports performance as the knowledge of how much and what products you should be eating. Equipped with this information you can make sure your body has the necessary nutrients to grow or enough space to lose weight while having the best potential to maximize effects of training.

[space_40]

What are calories and why are they so important?

[space_20]

In case your chemistry knowledge is a bit all over the place, allow me to quickly refresh your memory on the scientific definition: 1 calorie is the amount of heat required to raise the temperature of one gram of water from 14.5°C to 15.5°C. In many official publications you will see calories used interchangeably with Joules. 1 calorie = 4.184 Joules.

Energetic value of food is measured in calories not by accident. Heat is something very important for us, without some way of preserving it we can’t survive for very long in unfavorable conditions. Our body temperature needs to be stable at all times, and even small variations can cause us discomfort. Few degrees up or down – and our lives are at stake.

Think of human body as a biological machine powered by chemical energy – this energy is obtained from metabolizing food and by-product of that imperfect process is heat. A little bit like a diesel engine. With cars, the goal is to convert fuel into kinetic energy of a moving automobile. The engine also gets really hot in the process, because it kind of sucks at utilizing all available energy without a lot of it being lost and escaping the system as heat.

By evolutionary design, humans are not using all the energetic potential food provides us with either, but compared to other „machines” we’re actually ahead of the efficiency curve.

[space_40]

Introduction to TDEE

[space_20]

We all know what happens when our cars run out of fuel. No gas/diesel, no driving around and everyone stays at home or goes on foot (using up their own precious energy). However, the car has the ability to tell us when it’s low on fuel thanks to drivers best friend (and sometimes his biggest enemy) – the fuel gauge.

With human body, the need for fuel comes to us naturally – we feel hungry, we go out and buy food, then eat it. When we don’t feel hungry, this usually means the body has enough fuel to run for a while, so it gives us a break. Sort of a natural fuel gauge, except sometimes you just can’t stop yourself from overfilling the tank.

And so issues usually start when this gauge isn’t enough to optimize our health or performance. Despite best efforts, the weight doesn’t budge – or even worse, it shifts the other way, exactly where we don’t want it to go. Slowly we start warming up to the idea of estimating exactly how much it is that we eat – so finally we can take control of our physical appearance. AKA calorie counting. Most people never weigh food which goes into their meals, instead relying on their internal appetite control mechanisms to tell them when they’ve had enough. And with the exception of some who are blessed with the right combination of genes, those mechanisms are far from perfect in the rest of us.

Unfortunately, weighing your food seems to often carry negative connotation among those who do not fully understand the purpose behind it. It might be useful to compare food preparation during dieting to following recipes when cooking a complicated meal for the family or baking a cake – measuring everything guarantees the end result is right(or very close to). Nobody wants to spend time in the kitchen only for the meal turn out to be a failure. Measuring and weighing food while dieting achieves exactly what following a recipe in baking does – you know you’re getting the right amounts of all ingredients – which in turn will allow for the final product (your physique) to be a success and not a potential waste of time.

So think of your meal prep as a process of getting the right amount of each macronutrient (mostly carbohydrates,protein and fat) to help you achieve the desired result. Macronutrients have set caloric value per 1 gram and, when summed up, add up to a number – the number of all calories consumed in that meal. If calories consumed equal calories needed to maintain current weight, you will neither gain nor lose any. With the exception of some medical conditions (like thyroid issues or other problems of hormonal or metabolic nature, parasites etc.), as long as you eat around your weight maintenance calories (or „TDEE„) your weight will be stable. From this point affecting weight gain (or loss) is a process of managing your calorie intake versus your TDEE.

[space_40]

So! What is TDEE exactly?

[space_20]

It’s an acronym for Total Daily Energy Expenditure. Weight maintenance is achieved when your average daily calorie intake is equal to your average TDEE over a period of time. Like in accounting where the sum of your business expenses (calories out) cancels out your gross income (calories in) at the end of the month. This [ Calories In / Calories Out ] system even has it’s own acronym – CICO.

And just like in accounting, you can end up being on the positive side of CICO (called surplus), when your total daily energy intake (CI) is higher than your total daily expenditure (CO). This is how you gain weight, as the extra calories are stored in your body for potential future use. Or you can end up on the negative side (deficit) when your calories consumed are less than your TDEE. This is how you lose weight, as your body mobilizes internal energy stores to make up the difference betwen CI and CO.

[space_20]

In order to better understand TDEE we can break it down into following sections:

- BMR – Basal Metabolic Rate. Energy required to power up the various involuntary biological systems inside human body, like temperature maintenance, breathing, blood circulation along heart function, nervous system and so on. For most sedentary or lightly active people, this the largest portion of their TDEE – in some cases as much as 70%. For some very active individuals, it can be 50% or even less of their TDEE. [space_20]

- NEAT – Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis – this is everything that doesn’t fall under BMR/TEF which is essentially all our activity throughout the day – with the exception of exercise. This includes blinking, driving, sitting, fidgeting, furiously typing on the keyboard while arguing over the internet… Oops.[space_20]

- TEF – Thermic Effect of Food – BMR does not account for energy used to process and oxidize food. Consuming a meal has a temporary increasing effect on our TDEE. The more we eat, the higher TEF is, still it is a rather small portion of TDEE, usually around 10% but could be a little higher or lower as different nutrients require different amount of energy for processing, some are metabolically more efficient – like fat, some not so much and take a heavier toll on our body – like protein. TEF is then a result of total quantity and quality of food consumed over time and is not affected by the number of meals/servings.[space_20]

- EAT – Exercise Activity Thermogenesis – calories burned due to exercise, both in a direct way and in lingering effect it has on our physiology. If you don’t exercise at all, your EAT equals zero.

[space_20]

TDEE = BMR + NEAT + TEF + EAT

TDEE could also be affected by extremes of the environment if you’re not sheltered from those – but it appears changes in ambient temperature affect energy expenditure rather indirectly – possibly through behavioral changes during waking hours [study] as long as shivering is not induced. Shivering actually burns substantial number of calories, though I definitely don’t recommend that as a weight loss aid. It also changes during sickness and when taking certain types of medication/drugs.

Word on Adaptive Thermogenesis: a mechanism affecting your metabolic rate depending on calorie intake over time. It simply means you’re expending more calories just by eating at surplus and less when in deficit. AT makes maintaining stable weight after period of dieting down harder, and preventive measures like re-feeds and diet breaks should be taken to minimize AT when losing weight. You don’t really need to be concerned with adaptive thermogenesis as long as you control your daily calorie intake and react to changes in body composition.

[space_40]

Calculating your TDEE

[space_20]

Here you will find a step-by-step guide to obtaining accurate prediction of your calorie expenditure. It isn’t really necessary for you to know all this in order to start losing or gaining weight – you can simply use my Calorie Calculator. However, if you want to learn a bit more about the estimation process then continue reading. One last thing – I’m using BMR value on a few more occasions throughout this guide, so it might be helpful to complete the first step found below (although I definitely encourage you to go through all of them!).

[space_20]

Estimating your TDEE is neither hard nor complicated, though it might look that way at first glance.

I’ve divided the process into three simple steps. As a step number 1 we need to establish the biggest portion of TDEE – Basal Metabolic Rate(BMR).

[space_20]

Step 1.

BMR calculation is done through one of the best known today formulas called Mifflin-St Jeor, from the names of two lead researchers, who in 1990 have presented us with revised 70-year old formula, one that even more accurately predicts energy expenditure (by about 5%). Mifflin and St Jeor were also so kind to provide us with a simplified formula to calculate BMR in case we know the exact percentage of body fat (Fat-Free Mass formula). With much easier access to DXA equipment these days this information is fairly easy and inexpensive to obtain. If you had a DXA scan recently you can use the second formula for better precision, but in great majority of cases Body Weight formula does a very good job at estimating BMR.

- BMR Body Weight Formula: 9.99 x weight (kg) + 6.25 x height (cm) – 4.92 x age (years) + 166 x sex (males, 1; females, 0) – 161

- BMR Fat-Free Mass Formula:19.7 x FFM (kg) + 413 (same for both sexes, use only if you have fairly precise measurement of your body fat)

My BMR worked out at 1706 calories, two more steps to go!

[space_20]

Step 2.

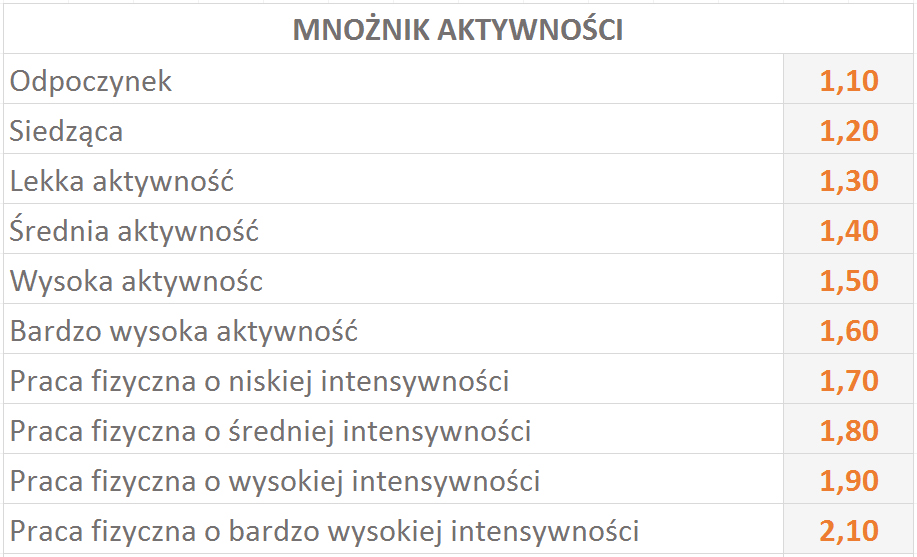

Choose an Activity BMR Multiplier closest to your usual level of activity. This does not include exercise and assumes you are already adapted to this lifestyle. Under the multiplier table you can find detailed description of possible options which should help with narrowing down your choice.

[space_20]

Odpoczynek = cały dzień w łóżku bez możliwości ruchu [1.10] większość dnia w łóżku za wyjątkiem wycieczek do kuchni/toalety [1.15] (22-24 godzin w pozycji leżącej)

Siedząca = cały dzień w pozycji siedzącej [1.20]. Cały dzień w pozycji siedzącej za wyjątkiem wycieczek do kuchni/toalety [1.25] (14-16 godzin w pozycji siedzącej)

Lekka aktywność = praca w biurze, typowa ilość ruchu w ciągu dnia (zakupy, sprzątanie, gotowanie itd.) większość osób nie pracujących fizycznie powinna tu zacząć [1.30] Podobnie, ale z większą ilością stania w miejscu (np. sprzedawca za ladą w sklepie, pracownik w fabryce przy taśmie) [1.35]

Średnia aktywność = sporo stania w miejscu i trochę chodzenia włącznie z lekką fizyczną aktywnością jak układanie towaru na półkach [1.40] podobnie, ale mniej stania i więcej chodzenia (np. ochrona w supermarkecie) [1.45]

Wysoka aktywność = praktycznie cały czas w ruchu przez kilka godzin (listonosz na pół etatu) [1.50] praktycznie cały czas w ruchu przez 8 godzin w ciągu dnia [1.55]

Bardzo wysoka aktywność = jak wyżej, ale wyższa intensywność ruchu [1.60] i [1.65]

Praca fizyczna o niskiej intensywności = cały dzień na nogach, noszenie przedmiotów, dość męcząca praca [1.70 – 1.75]

Praca fizyczna o średniej intensywności = j/w ale większa intensywność, bardzo męcząca praca (pomocnik na budowie) [1.80 – 1.85]

Praca fizyczna o wysokiej intensywności = chodzenie, noszenie ciężkich przedmiotów cały dzień, kopanie rowów, ekstremalnie męcząca praca [1.90-2.05]

Praca fizyczna o bardzo wysokiej intensywności = j/w ale 10-12 godzin w ciągu dnia [2.1+]

Please keep in mind this is only your starting point. Multiplier table is not perfect and won’t work the same for everyone, still it’s probably as accurate as you can get without direct ways of measuring your calorie expenditure (like an all-inclusive stay at metabolic ward). It should however get you pretty close to your true TDEE. Once you can observe the rate at which your physique changes you can make finer adjustments to these numbers.

Now that you have picked your Multiplier, all you need to do is perform a simple calculation of BMR x Multiplier. As a result you will get a number, which is your BMR+NEAT+TEF combined. This is your Non-Exercise Daily Energy Expenditure. If you performed zero exercise during the week, this would be your only number to consider for every day with similar level of activity. And what if you want to exercise? Jump ahead to step 3 and find out. Oh and by the way my Non-Exercise DEE worked out at 2132 calories. We’re getting pretty close!

[space_20]

Step 3.

Estimate your EAT (Exercise Activity Thermogenesis)

Take your BMR – we calculated it in step one (mine was 1706) and multiply it by 0.21. For me it worked out at 358. This number is the amount of calories you are likely to burn over 1 hour of moderate (50%) intensity endurance exercise – like jogging – or over 1 hour of weight training. For higher intensity exercise like running or swimming you can multiply your BMR by 0.315 or even 0.42 (for close to max effort training like sprinting/HIIT etc.). For lower intensity exercise – like walking 5 km/hour – multiply it by 0.16 (and for me this means 272 calories / hour) or 0.12 if it’s even lower effort. Tying EAT to BMR allows us to make it dependent on your lean body mass – and therefore likely more accurate.

Once you’ve got your EAT add it to your BMR x Multiplier to obtain your TDEE. You can calculate separate TDEE’s for your training day/cardio day/rest day etc.

[space_20]

Once you have obtained these numbers and decided on either deficit, surplus or maintenance, you should stick to your choice for the first four weeks of your diet and write down your weight every day. By observing the changes in body weight over this period you can make any additional adjustments to your TDEE in small increments of 100 calories until you achieve desired degree of weight loss/gain or your average weight stabilizes if your goal is maintenance.

[space_40]

Macronutrients

[space_20]

Thanks to the advancements in nutritional sciences of the 20th century we have identified core food components and assigned caloric value to them – those are proteins, carbohydrates, fats and alcohol. By taking a single example – an apple – and adding up the caloric value of all of its macronutrients we will obtain approximate total caloric value of that product – reason I’m using the word „approximate” is because there are some minor differences between countries due to law and how it allows manufacturers to report calories for fractional macronutrients as well as fiber content.

For example, in the US food labels show calories per serving, with serving being the arbitrary number manufacturer decides on – and if the caloric value of one serving is less than 4, they are allowed to report zero calories. This is why cooking oil spray can have officially zero calories per serving, despite the fact that it obviously contains calories in every serving no matter how small. Another example: if serving size of popular mint candy is „one piece” which is less than 4 calories, it is labeled as having none – whereas a box of 30g can easily provide 80-100 calories. Last example: fiber content. Some countries allow for fiber to be shown on label as not containing any calories, however US FDA assigns an average value of 1.5 calorie per 1 gram of fiber. This way high fiber foods could be potentially under-reporting calorie content. This is why it’s important to use reliable sources for calorie & macronutrient information.

[space_40]

Below are the macronutrients you can find on food labels along with their short description and rounded/mean caloric value:

[space_20]

[columns] [span4]

Building blocks of human body. Without sufficient amount of protein in diet our body starts disassembling your muscles in order to provide those necessary blocks in effort to create new tissues. Lack of protein stunts growth in children, decreases satiation from meals and causes a whole range of negative physiological effects. Protein – just like water – is life, though of course there is such a thing as too much of both. Recommended daily amount of protein is pretty much the same everywhere and it varies little between untrained individuals – men have slightly higher requirement compared to women due to higher amounts of lean mass. However we need to remember that recommended does not equal optimal for individuals undergoing regular physical training. Economically, protein is an expensive macronutrient.

1 gram of protein = 4 calories.

[/span4][span4]

Often quoted separately on food labels, fiber is a form of only partially digestible(and some is indigestible) carbohydrate. Why are carbohydrates important? They are a primary source of glucose for humans. Our physiology is largely centered around availability of glucose, though human body can operate in low glucose scenarios as well, it is not necessarily as efficient. Blood sugar? Glucose. Glycogen? Glucose. There are large variations between individuals as to what portion of energy content coming from carbohydrates makes them feel at their best. Like with most things related to health and well-being, there are government established general guidelines for carbohydrate consumption (and separately sugar, a simple carbohydrate) which change depending on country you live in. And fiber? Colon cancer prevention, gut health and slower gastric emptying are just a few benefits. Economically carbohydrates are the cheapest macronutrient.

1 gram of carbohydrates = 4 calories

1 gram of fiber = 1.5 calories (mean)

[/span4][span4]

Most energy dense macronutrient per unit of weight – fat has been demonized over the years and still stands as an easily misunderstood element of diet. If there is one thing I wish you remembered about fat, is that it is necessary for our well being and, by itself, is not harmful at all when consumed from unprocessed sources as a part of eucaloric diet (a diet which has been designed to maintain weight). Why unprocessed? Because some processed fats can be bad for you, and some like hydrogenated fats don’t have a single redeeming quality about them – they are just bad, period. Economically, fat is a moderately expensive macronutrient.

1 gram of fat = 9 calories

[/span4][/columns]

[space_20]

Some of you might already be saying „What about alcohol? You mentioned alcohol is a macronutrient”. Correct! Alcohol contains 7 calories per 1 gram (500ml beer contains roughly 25 grams of alcohol), and takes metabolic precedence before every other macronutrient. It also isn’t required for anything in human physiology, so technically there is no need to include it in a health or performance oriented diet. In fact, if our ancestors didn’t decide on eating slightly fermented fruit, we would likely be unable to process alcohol at all.

It is worth mentioning that alcohol consumption limited in both quantity and frequency will have negligible negative effects on body composition and performance. On the other hand consumption of more than 50% of your calories from alcohol can result in malnutrition and fatty liver disease.

[space_40]

Relation between body composition, calorie and macronutrient intake

[space_20]

All right! With the current state of research into human physiology and nutrition sciences we can make the following general statements:

- Caloric surplus is the primary cause behind weight gain(both fat and lean mass), degree of which is affected by diet macronutrient breakdown to a small degree. This is because of different TEF for protein, carbohydrates and fat(protein being the highest). In theory, at high protein intakes (50%+ calories from protein) in caloric surplus fat gain could be little lower versus conventional diet (assuming calorie intakes were the same) but those are not your typical real world conditions (and there is no need to ever consume this much protein in caloric surplus) and the gains in TEF are minimal (below 5%) [review][space_20]

- Caloric surplus allows for increased anabolism – promotes new tissue creation and reduces tissue breakdown. This means both lean mass and fat mass increase in varied proportions based on diet, type and effectiveness of physical training with more individual factors at play(genetics and training advancement being two major ones). Long-term overfeeding however doesn’t just influence fat and lean mass accumulation, but also increases levels of blood lipids, promotes insulin and leptin resistance, opens up the way to a number of potential metabolic diseases and puts more strain on the digestive system. Cardiovascular health becomes primary concern in long term caloric surplus and growing trunk size.[space_20]

- Caloric maintenance allows for balance between anabolism and catabolism, resulting in neither substantial gain nor loss of tissues over time, assuming adequate protein intake. Introducing resistance training allows for making positive changes in body composition, specifically accretion of muscle tissue – degree of which is based on diet, training program and other individual factors, though it does not occur as fast as when in caloric surplus.[space_20]

- Caloric deficit increases catabolism – tissue breakdown while suppressing tissue creation to necessary minimum. Size of caloric deficit as well as time spent in deficit are two primary factors behind rate of weight loss. High deficit allows for faster weight loss, but also triggers adaptive thermogenesis and appetite regulation mechanisms to greater degree than slower, more sustainable weight loss at lower deficit. There appears to be a maximum rate of adipose tissue triglyceride conversion to energy over time which is dependent on fat tissue availability[study](though this number is nowhere near established or even confirmed and likely is much lower) therefore higher deficit places leaner individuals at risk of greater muscle loss. Another variable behind adaptive thermogenesis I mentioned is time spent in deficit[study] and as of right now the consensus seems to be for weight loss to have intermittent rather than persistent nature, with re-feeds and periods of weight maintenance allowing for psychological relief as well as promotion of positive hormonal changes(specifically regulation of thyroid/androgen/estrogen levels) and reductions in appetite. Lastly, in order to increase chances for successful weight loss and minimize losses in lean body mass, outside of well designed diet a resistance training program should be employed (or at least higher intensity cardiovascular training and bodyweight training). Some positive adaptations in caloric deficit outside of weight loss are increased leptin and insulin sensitivity, improvements to blood lipid profile and therefore reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. Animal studies suggest potential for increased lifespan. In other words – intermittent caloric deficit not only has the potential to make you look better, it also offers significant health improvements.

[space_40]

Practical recommendations for caloric intake

[space_20]

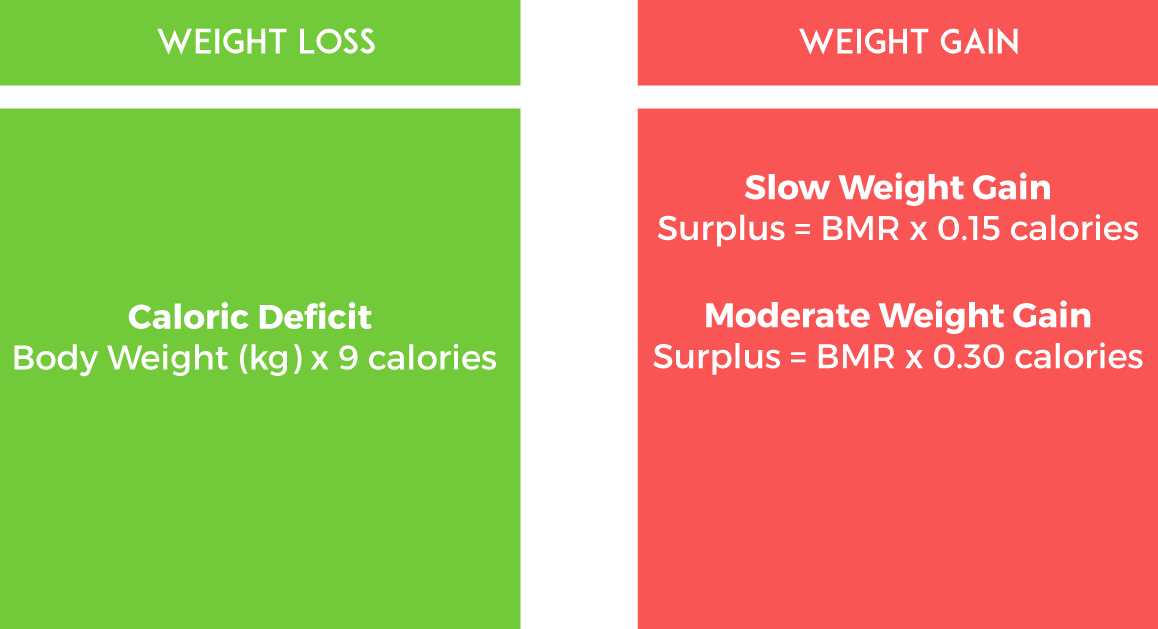

Below you can find simplified guidelines for sustainable weight loss and controlled weight gain.

Please note: if you’re on the leaner side (and see some abdominal definition visible) use between 70-80% of the suggested caloric deficit. If on the other hand you’re carrying a lot of extra body fat you could go up to 120-130% of the calculated caloric deficit as your body will be able to obtain more energy from your fat stores without triggering higher degree of adaptive thermogenesis too soon.

[space_20]

[space_20]

Calorie recommendations for weight loss are based on following research:

Body fat content influences the body composition response to nutrition and exercise. Forbes GB – Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000, 904: 359-365.

Body fat and fat-free mass inter-relationships Br J Nutr. 2007, 97: 1059-1063. 10.1017/S0007114507691946.

What is the required energy deficit per unit weight loss?. Int J Obes. 2007, 32: 573-576.

Effect of two different weight-loss rates on body composition and strength and power-related performance in elite athletes. – Garthe I, Raastad T, Refsnes PE, Koivisto A, Sundgot-Borgen J – Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2011, 21: 97-104.

A limit on the energy transfer rate from the human fat store in hypophagia: J Theor Biol. 2005 Mar 7;233(1):1-13. Epub 2004 Dec 8 (revised number based on an e-mail correspondence with researcher)

Evidence-based recommendations for natural bodybuilding contest preparation: nutrition and supplementation – Eric R Helms,Alan A Aragon and Peter J Fitschen

[space_20]

Calorie recommendations for weight gain are based around Alan Aragon’s Muscle Gain Model and the McDonald’s Model. The desired rate of weight gain also takes into consideration your fat-free mass (more muscle = greater surplus required to optimally rebuild and compensate). However, since everyone gains muscle mass at different rate, for one individual „slow” option will offer the biggest benefit – persistent muscle gains with low fat gain, whereas for someone else moderate weight gain might be better, as their rate of building muscle tissue is faster either due to optimized recovery, well designed training program or genetic factors (or a combination of all those). Individuals with long training history build muscle at slower rates due to being closer to their genetic potential, while beginners make much faster progress. An average small beginner typically will gain less muscle mass compared to a large beginner, so having a fixed rate of surplus for a petite woman and a big, tall guy wouldn’t likely provide optimal results for neither. Here are my recommendations:

- beginners to weight training – moderate surplus is likely to be the best option.

- intermediate – if you have not observed faster fat gain with moderate surplus until now, you can continue with it until it stops being efficient (ie. you notice gaining more fat than muscle after weight gain cycle).

- advanced – it’s likely you aren’t making much progress at this point as you’re approaching your natural genetic potential, hence why I would typically recommend slow&steady weight gain to minimize fat accumulation.

[space_40]

Practical recommendations for macronutrient intake

[space_20]

By now you have likely used BMR value on several occasions and here is yet another one. A simple reverse engineering of the Fat-Free Mass(FFM) equation by Millfin-St Jeor will get you a FFM/LBM estimate (Lean Body Mass, everything that’s not fat), something that will help with estimating optimal protein intake. So unless you’ve had a BodPod or DXA done recently, use the result of the following formula(both men and women):

[space_20]

Fat Free Mass (LBM) in kg = (BMR – 413) / 19.7

[space_20]

Now it’s time for the good stuff: macronutrient recommendations!

[space_20]

[columns] [span4]

Weight Loss:

2.3 – 3.1 grams per 1kg of LBM depending on severity of caloric restriction

Weight Gain:

1.8 – 2.2 grams per 1kg of LBM

[space_20]

Above recommendations are for individuals undergoing physical training with a sufficient level of volume and intensity to promote adaptations within muscle tissue but even for someone who doesn’t exercise increased protein intake at the cost of carbohydrate and fat has many advantages.

[space_20]

Sources:

[review] [review] [review] [review]

[/span4][span4]

Weight Loss & Weight Gain:

Both simple & complex carbohydrates help with performance and seem to improve sense of meal satisfaction but can also decrease satiation. Best option is to modulate fat to carbohydrate intake ratio depending on the amount of activity and overall sense of well-being – someone who works out 2-3 times per week will need less carbohydrates overall than someone who works out 6 days per week. Considering that there is a minimal amount of fat you should ideally provide as well as a set amount of protein, the leftover calories could come from carbohydrates. You should also consider replacing calories lost exercising with carbohydrates to aid in glycogen and muscle recovery, then adjust them further up or down based on perceived hunger and energy levels to find the right balance for yourself. For losing weight, assuming you did not overshoot with the deficit you should be able to establish those ratios within the first few weeks of your diet.

[space_20]

Fiber: 25-30 grams per day minimum as per UK/US Dietary Recommendations. Higher fiber intakes (40g+) can help with hunger control during weight loss, but are best introduced slowly and require adequate water consumption to avoid gastric issues.

[space_20]

Sources:

[/span4][span4]

Weight Loss:

15%-20% of total calorie intake, but possibly higher on some days if cycling cabohydrates.

Weight Gain:

20-30% of total calorie intake

[space_20]

Sources:

[/span4][/columns]

[space_40]

Meal timing and „anabolic window”

[space_20]

There is sufficient evidence emerging that more frequent timing of your meals in caloric deficit can be beneficial to lean body mass retention [review]. In trained individuals with sub-optimal intake of protein while in severe caloric restriction more frequent feeding pattern plays a role in preserving LBM [study], most likely thanks to a series of acute increases in muscle protein synthesis suppressing protein breakdown and higher efficiency of protein utilization when consumed over several meals instead of one or two sittings. However, with less severe caloric deficit and adequate protein intake, those differences would likely be not nearly as pronounced.

Still, consuming between 3 and 5 meals containing at least 20 gram of complete protein (typically more, refer to my earlier macronutrient intake recommendations) is a good idea, yet without doubt the greatest predictors of lean body mass retention (or even gain) during weight loss are severity of caloric deficit, presence of weight training program and total amount of protein consumed [study].

In caloric surplus, assuming adequate protein intake, LBM retention is not an issue but instead increase in muscle hypertrophy usually is the goal. In part because of „muscle full” effect [review] spacing out your meals in order to maximize rates of muscle protein synthesis seems beneficial, however the main factor behind hypertrophy in presence of sufficient stimuli (weight training) is the total amount of calories and protein consumed while the size of „anabolic window” being greater than previously believed, with not just post-workout but also pre-workout nutrition capable of stimulating growth [review].

[space_40]

Closing thoughts

[space_20]

There are two fundamental factors responsible for vast majority of progress in changing body composition – managing your calories and ensuring adequate protein intake. While more advanced options exist which help in achieving optimal results, it’s important to stress that adherence to these basic rules in light of your goals is all you need to kick-start your quest for a more fit, aesthetic and healthy body.

From my own experience, I’d like to add one thing to all this: while achieving your goal definitely matters, usually there is a long path that leads to it. It’s very important to enjoy the journey along that path. So unless you are a physique competitor or a professional athlete( in which case you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do), don’t ever allow fine details of nutrition to take precedence before all the other important things in life, like your family, friends or your job. Especially with weight loss, it’s better to take a little longer to get there and enjoy socializing and other fun activities in life along the way (of course in a way which still allows you to stick onto your diet most of the time), rather than being miserable and unhappy, always munching on your broccoli alone in the corner – and trust me I know something about that as well. Of course if you’re in the minority who adhere to diet better by imposing full restriction – then that’s what you should do! In the end, weight loss is just the beginning of the process – maintaining your new physique and improving on it is where the fight is, and it’s the one that lasts for the rest of your life.

Thanks for reading!

– Konrad